On November 2, 2024, BloodHorse reported that Jayarebe, a participant in the Breeders’ Cup Turf, “suffered an apparent heart attack and died after finishing seventh in the 1 1/2-mile race at Del Mar.”

The report stated that Jayarebe “suffered an apparent heart attack.” At first glance, this wording might seem harmless. However, a closer look reveals how the misuse of “apparent” blurs the clarity of the statement, introducing an unnecessary ambiguity.

When journalists use “apparent” in this way, it’s easy to imagine what they mean—that Jayarebe likely died from a heart attack. Yet, the phrase “apparent heart attack” suggests that the heart attack was only a possibility, not a confirmed cause of death. In reality, Jayarebe didn’t suffer from an “apparent” heart attack; the horse either died from a heart attack, or the actual cause was unknown. It’s a subtle but important difference, especially when precise language matters.

In her book Write and Wrong, Martha Johnson explains the common misuse of “apparent” and “evidently” with examples. She writes, “Apparent is a sad case. Journalists and other writers regularly do violence to it.” Johnson’s examples highlight how words like “apparent” and “evidently” often turn up where they don’t belong, muddying what could be a clear statement.

Take, for example, the sentence, “He died of apparent asphyxiation.” This phrasing implies a kind of tentative diagnosis, but people don’t die from “apparent” anything. Instead, Johnson suggests that “The apparent cause of death was asphyxiation” is more accurate, conveying that asphyxiation is the suspected cause without committing to it as fact. The distinction here lies in framing “apparent” as an adjective for the cause, not the event itself. We can have an “apparent cause” when we lack conclusive evidence, but “apparent death” or “apparent heart attack” is confusing at best and misleading at worst.

The same nuance applies to “evidently,” another word often suffering in the hands of writers eager to sound authoritative. In Write and Wrong, Johnson explains how “evidently” can be misused: “She has a high score; she’s evidently the winner.” While it may seem that her high score points to her victory, this statement assumes too much. Without knowing any other scores, “evidently” becomes premature, creating an assumption rather than conveying a fact. A clearer alternative might be: “She scored 100; she’s the apparent winner,” indicating that, based on available information, she seems to be in the lead.

To use “evidently” correctly, there must be some form of evidence backing up the claim. Johnson suggests that a sentence like “The forest is evidently being destroyed by spruce beetles” would imply that tests or studies have been conducted, showing the beetles’ role in the forest’s decline. Without that evidence, the writer might instead say, “The forest is apparently being destroyed by a spruce beetle plague,” which signals that we’re observing signs of damage without a confirmed cause.

In the BloodHorse report, the choice of “apparent” highlights how small word choices can significantly impact clarity. If the cause of Jayarebe’s death was truly unknown, it might have been clearer to say, “Jayarebe collapsed and died, possibly from a heart attack.” This phrasing leaves room for uncertainty without suggesting that a heart attack is only “apparent.”

The misuse of “apparent” and “evidently” often stems from a desire to avoid definitive statements when all facts aren’t available. Yet, there’s a way to maintain precision and honesty without ambiguity. By framing uncertainty more accurately—whether as an “apparent cause” or using “evidently” only when evidence exists—writers can convey the situation truthfully and clearly.

These two words remind us of the power of specificity in writing. Each word in a sentence should carry weight and purpose. When used correctly, “apparent” and “evidently” can enhance clarity; when misused, they only add fog. For writers, especially those in journalism, where factual accuracy is paramount, understanding the nuance of language is more than a stylistic choice—it’s a responsibility.

So, the next time you find yourself writing about an “apparent” heart attack or using “evidently” without supporting evidence, take a moment to reconsider. These minor adjustments don’t just clean up your prose; they respect the reader’s intelligence and trust, allowing your message to come through with the accuracy it deserves.

We Don’t Want to Write the Laws; We Want to Publish the Books

Publication Consultants: The Synonym for Book Publishing—https://publicationconsultants.com

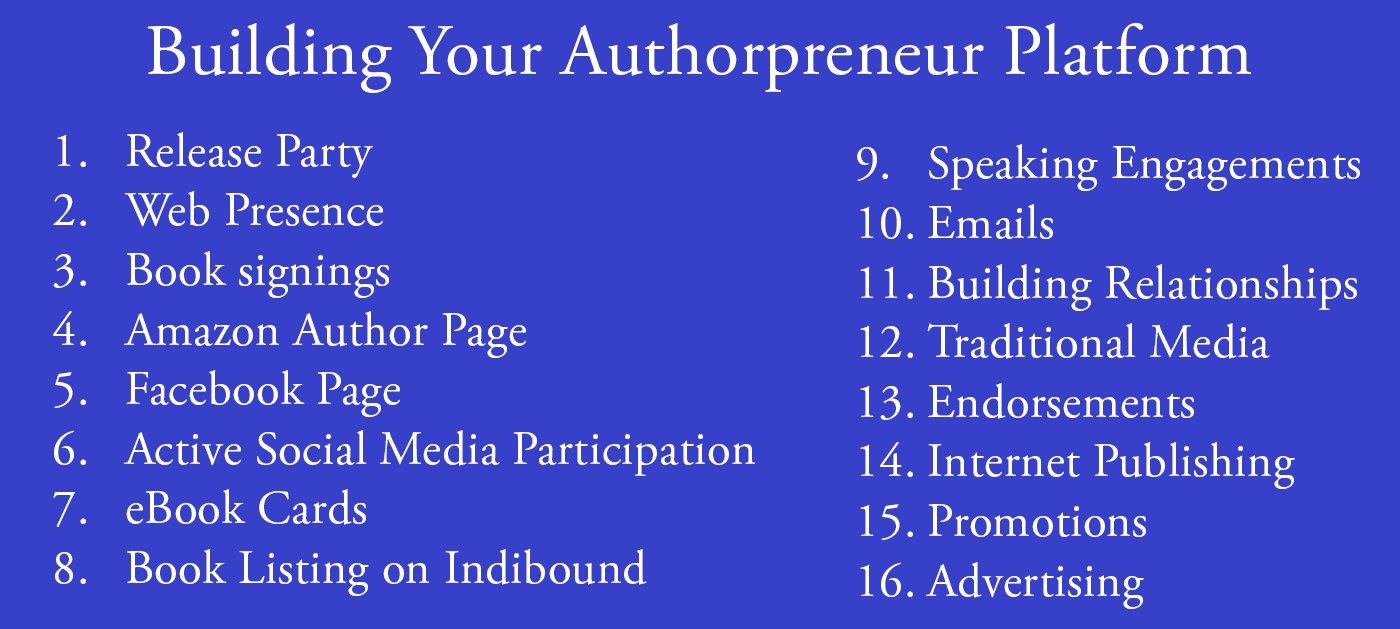

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them. Release Party

Release Party Web Presence

Web Presence Book Signings

Book Signings Facebook Profile and Facebook Page

Facebook Profile and Facebook Page Active Social Media Participation

Active Social Media Participation Ebook Cards

Ebook Cards The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

Costco Book Signings

Costco Book Signings eBook Cards

eBook Cards

Benjamin Franklin Award

Benjamin Franklin Award Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex.

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex. Correction:

Correction: This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

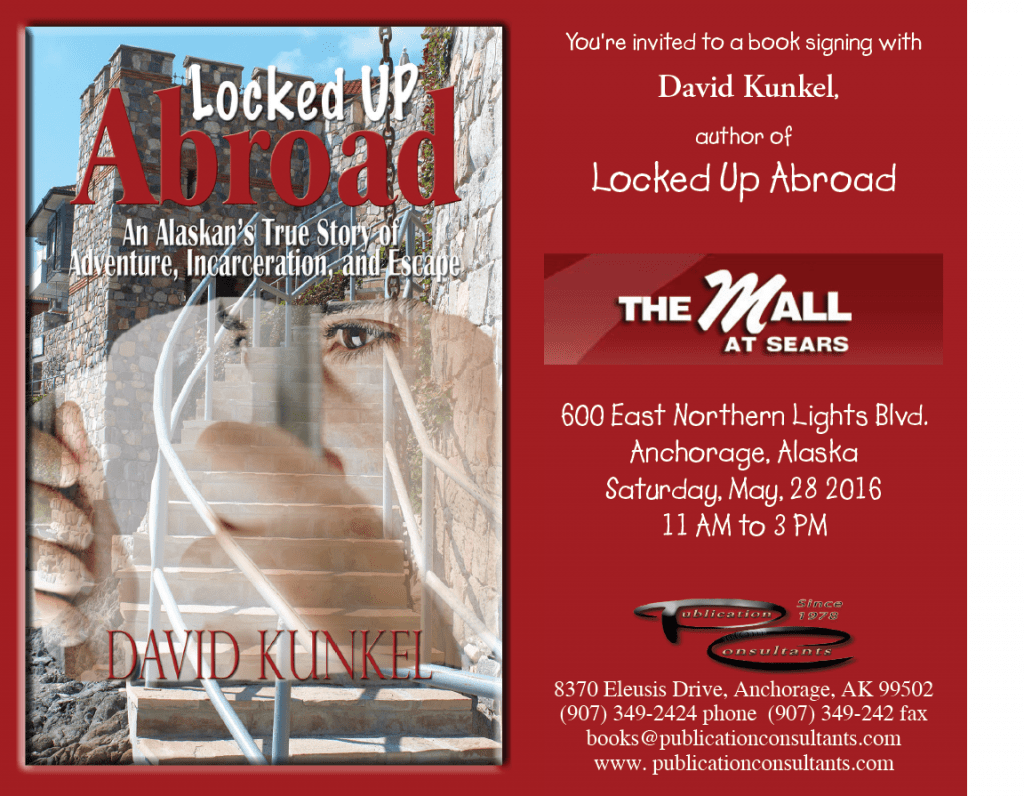

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, <

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, < We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

Time and Tide

Time and Tide

ReadAlaska 2014

ReadAlaska 2014 Readerlink and Book Signings

Readerlink and Book Signings

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores.

When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores. More NetGalley

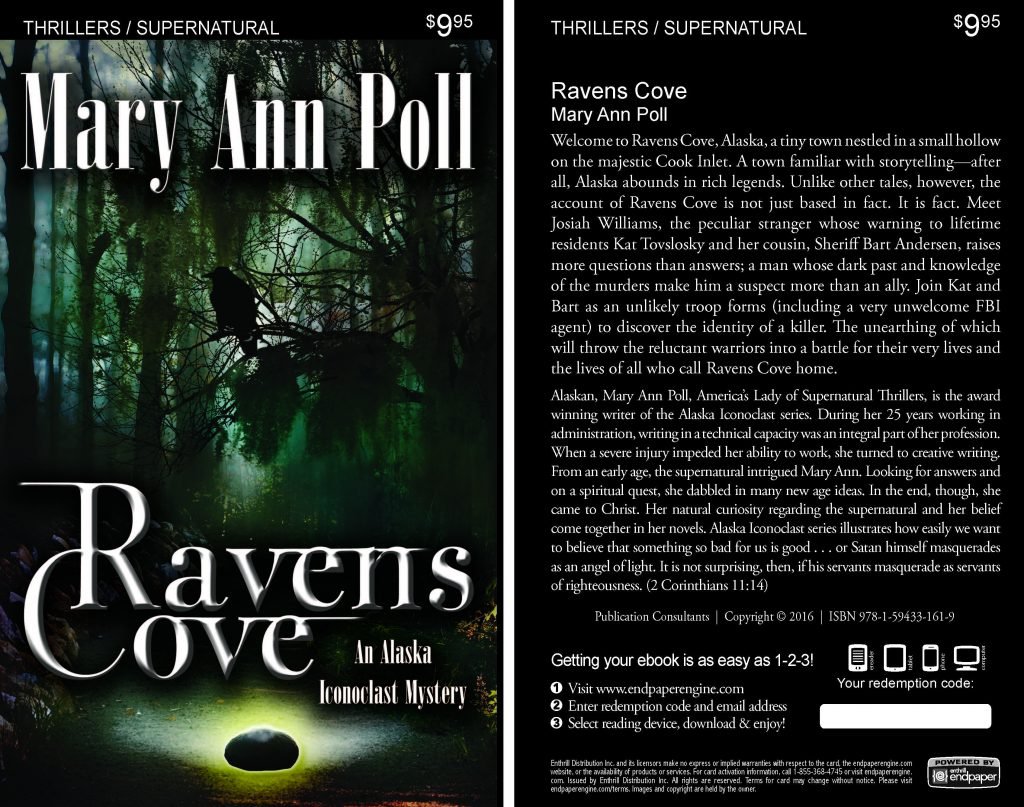

More NetGalley Mary Ann Poll

Mary Ann Poll

Bumppo

Bumppo

Computer Spell Checkers

Computer Spell Checkers Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email

Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email 2014 Spirit of Youth Awards

2014 Spirit of Youth Awards Book Signings

Book Signings

Blog Talk Radio

Blog Talk Radio Publication Consultants Blog

Publication Consultants Blog Book Signings

Book Signings

Don and Lanna Langdok

Don and Lanna Langdok Ron Walden

Ron Walden Book Signings Are Fun

Book Signings Are Fun Release Party Video

Release Party Video

Erin’s book,

Erin’s book,  Heather’s book,

Heather’s book,  New Books

New Books