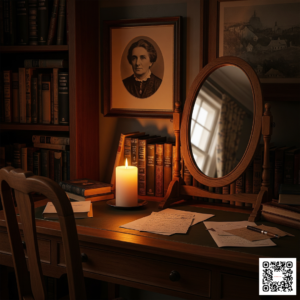

Edith Wharton’s quote, “There are two ways of spreading light: to be the candle or the mirror that reflects it,” captures the essence of influence and kindness in two distinct but equally valuable forms.

To be the candle is to originate light—to create, to lead, to ignite inspiration or hope. These are the innovators, the visionaries, the bold voices who blaze new trails. They bring warmth, clarity, and direction into darkness. Think of a teacher introducing a child to literature for the first time, or a friend who offers unwavering support during grief. The candle gives of itself—sometimes burning down in the process—but its flame can light a thousand others.

To be the candle is to originate light—to create, to lead, to ignite inspiration or hope. These are the innovators, the visionaries, the bold voices who blaze new trails. They bring warmth, clarity, and direction into darkness. Think of a teacher introducing a child to literature for the first time, or a friend who offers unwavering support during grief. The candle gives of itself—sometimes burning down in the process—but its flame can light a thousand others.

The mirror, in contrast, doesn’t generate light but reflects it. This is the quiet strength of those who amplify others’ goodness. A mirror listens, affirms, and helps others see their own brightness more clearly. A parent who cheers from the sidelines, a nurse who comforts with presence more than words, or a friend who celebrates your success as though it were their own—these are mirrors. They may not seek the spotlight, but they carry light just the same.

Wharton’s insight gently affirms everyone has a role in illuminating the world. Some will blaze forward, while others will reflect that radiance with equal grace. The key is not whether one is the candle or the mirror, but whether one chooses to shine at all.

Edith Wharton, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, lived in a world of rigid formality but wrote with an intellect sharp enough to dissect its hypocrisies. Born in 1862 into New York’s elite, Wharton grew up with chandeliers overhead and expectations closing in like lace-curtained walls. She became a master chronicler of upper-class society, not to flatter it, but to reveal its silent cruelties and emotional poverty.

Though admired for her prose, Edith Wharton’s life was not immune to hardship. Her marriage to Edward Wharton, a man whose mental health deteriorated over time, became a quiet sorrow. Society expected her to smile and entertain, not to write or think too deeply. Yet she carved out hours—mornings especially—for her craft. In a world where women’s voices were often muted, she published more than 40 books. Her writing became her protest, her survival, and her illumination.

The emotional distance in The House of Mirth feels less like fiction and more like autobiography. Lily Bart’s tragic arc stands as a mirror to the cost of appearances, especially for women. Wharton didn’t scream her defiance. She inked it carefully, each word a candle lit against pretense.

During World War I, Wharton lived in Paris. While many of her peers retreated into art or comfort, she turned outward. She organized relief efforts, raised funds, visited the front, and wrote war reports for Scribner’s Magazine. Her essay collections from this time, including Fighting France, carried both realism and reverence. Her friendship with Henry James had long encouraged her literary discipline, but the war deepened her humanity. She had every reason to remain in drawing rooms, yet chose to walk muddy roads instead.

Wharton’s fiction peeled away the polished veneers of old-money society. In The Age of Innocence, she didn’t merely portray a love triangle but exposed how societal codes could crush sincerity. The novel’s 1921 Pulitzer win made history. Yet her influence went further—she legitimized domestic realism as serious literature. She revealed how manners could be cruel and silence more devastating than action. Generations of writers—think Morrison, Sontag, even Franzen—owe a debt to her precision and moral clarity.

Wharton’s pen did more than tell stories. It held up mirrors to a culture unwilling to confront its own reflection. She proved writing could soften hearts, shift norms, and redefine what power looked like. Not with vulgarity or shock, but with sentences so polished they cut. Her work reminds writers that substance, not spectacle, defines lasting influence.

She was both candle and mirror—an originator of light and a reflection of what mattered.

Explore her novels, starting with The Age of Innocence or The House of Mirth. Read her war essays. Let them remind you why words matter. Then, write. Not louder, but truer. Light the way, or reflect it—but write.

Help Us Spread the Word

If this message inspired, informed, or gave something worth thinking about, please consider sharing it. Every share helps grow a community of readers and writers who believe in the power of stories to make a difference.

Please invite others to join us by using this link: https://publicationconsultants.com/newsletter/

Thank you. We’re always glad to have one more voice in the conversation.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them. Release Party

Release Party Web Presence

Web Presence Book Signings

Book Signings Facebook Profile and Facebook Page

Facebook Profile and Facebook Page Active Social Media Participation

Active Social Media Participation Ebook Cards

Ebook Cards The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

Costco Book Signings

Costco Book Signings eBook Cards

eBook Cards

Benjamin Franklin Award

Benjamin Franklin Award Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex.

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex. Correction:

Correction: This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, <

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, < We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

Time and Tide

Time and Tide

ReadAlaska 2014

ReadAlaska 2014 Readerlink and Book Signings

Readerlink and Book Signings

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores.

When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores. More NetGalley

More NetGalley Mary Ann Poll

Mary Ann Poll

Bumppo

Bumppo

Computer Spell Checkers

Computer Spell Checkers Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email

Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email 2014 Spirit of Youth Awards

2014 Spirit of Youth Awards Book Signings

Book Signings

Blog Talk Radio

Blog Talk Radio Publication Consultants Blog

Publication Consultants Blog Book Signings

Book Signings

Don and Lanna Langdok

Don and Lanna Langdok Ron Walden

Ron Walden Book Signings Are Fun

Book Signings Are Fun Release Party Video

Release Party Video

Erin’s book,

Erin’s book,  Heather’s book,

Heather’s book,  New Books

New Books

1 thought on “The Candle and the Mirror”

Thank you for this article about Edith Wharton — none of which I knew before reading it. I’ve sent it to my children and grandchildren for reflection as well. Thank you!