Charlie had successfully carried her four subsistence hunters to a proper conclusion. Each had taken a moose, dressed it out, and cut it up in pieces small enough to be carried in Charlie’s cockpit. The morning’s two hunters finished their field dressing, and Charlie ferried them to the small, snow-covered swamp to assist Charlie’s afternoon hunters in packing their winter’s moose meat from the swamp to a small but adequate-sized lake runway.

Charlie’s pilot left the four hunters to their work and loaded Charlie with moose meat from the morning hunters’ kill. Then, he guided Charlie back to Lake Hood, where the morning hunters’ family met the airplane and accepted the moose. Several more trips were taken in like manner until the first two moose were in Anchorage and on their way to the happy family’s freezer.

Now that the first two moose were taken care of, Charlie’s pilot turned to the last two. It was late afternoon, and the November sun was just above the horizon when Charlie started back to Anchorage with a load of meat and one of the hunters. Two more trips from lake in the woods to Lake Hood in Anchorage, and all but one of the hunters and an oversized load of moose remained in the field.

As Charlie’s pilot left the lake on his last trip, he gave the remaining hunter a flashlight and asked him to stand in the middle of the lake when he heard Charlie return. “Wave the light, and I’ll know what lake you’re on, and I can find you, and I can judge where to set Charlie down.”

Afternoon clouds had moved in when Charlie returned to the lake, and darkness had set in. Alaska’s winter nights seldom get pitch-black dark because of light reflected off of snow, so Charlie’s pilot could locate the moose lake. As Charlie came in over the trees, Charlie’s pilot saw the flash of a waving flashlight and set Charlie up for a landing judged by the location of the waving light. As Charlie’s skis felt the first touch of snow, pucker brush and hummocks seemed to grow out of what Charlie’s pilot thought was the lake.

Charlie bounced from hummock to hummock; willows beat at Charlie’s old red paint, and she finally slid to a stop on the lake’s ice. Charlie’s hunter came running, carrying the waving flashlight. “I didn’t mean for you to land here. I waved the light back and forth, signaling you not to land. There’s an old trapper’s cabin over there, and I’ve been visiting with the trapper. I didn’t think you’d get back so soon and wasn’t able to get out on the lake, so I tried to wave you off until I made the lake’s center.”

Charlie’s pilot was filled with quiet anger. The hunter’s actions had almost caused a serious accident. Charlie’s pilot took his anger out on the remaining moose meat by unkindly loading it into the airplane. By the time the moose was loaded, Charlie’s pilot’s anger had subsided, and he could speak without showing his frustration of nearly killing himself and wrecking Charlie.

“The plane’s full; I can’t take you on this trip. I’ll come back later,” Charlie’s pilot explained as he tied the meat in with seat belts and fastened his belt. “If I can’t make it back, see if you can stay with the trapper in his cabin, and I’ll see you tomorrow morning.”

With that, Charlie’s pilot cranked the starter, and Charlie once again motored into action and was soon airborne heading toward Anchorage. As the lights of Anchorage came into view, Charlie’s pilot made a decision. He wasn’t going back. He’d had enough excitement for one day. His subsistence-hunting buddy would have to subsist for the night. It’d be a long night for the hunter. But in daylight, Charlie’s pilot wouldn’t have to rely on a waving light to find the runway. At least that’s the line of rationalization Charlie’s pilot used to convince himself to leave his buddy overnight in 30-degree-below weather on a frozen lake within 30 minutes of Anchorage. He hoped the trapper was hospitable.

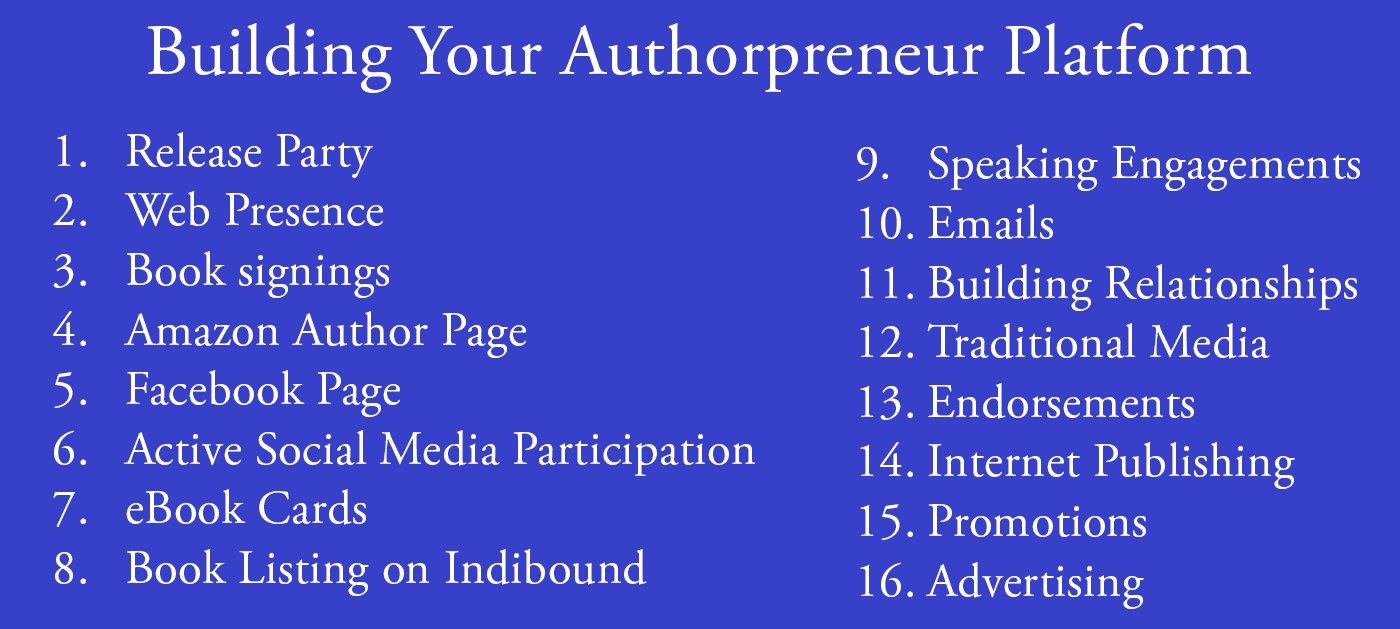

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them. Release Party

Release Party Web Presence

Web Presence Book Signings

Book Signings Facebook Profile and Facebook Page

Facebook Profile and Facebook Page Active Social Media Participation

Active Social Media Participation Ebook Cards

Ebook Cards The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

Costco Book Signings

Costco Book Signings eBook Cards

eBook Cards

Benjamin Franklin Award

Benjamin Franklin Award Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex.

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex. Correction:

Correction: This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

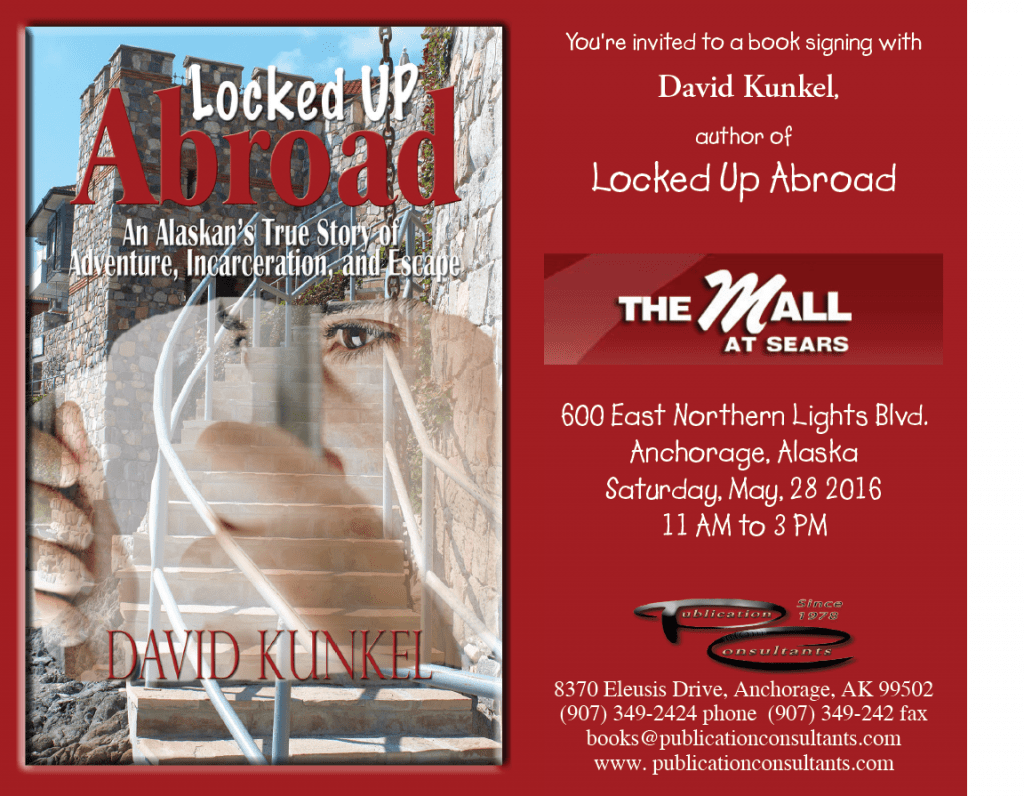

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, <

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, < We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

Time and Tide

Time and Tide

ReadAlaska 2014

ReadAlaska 2014 Readerlink and Book Signings

Readerlink and Book Signings

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores.

When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores. More NetGalley

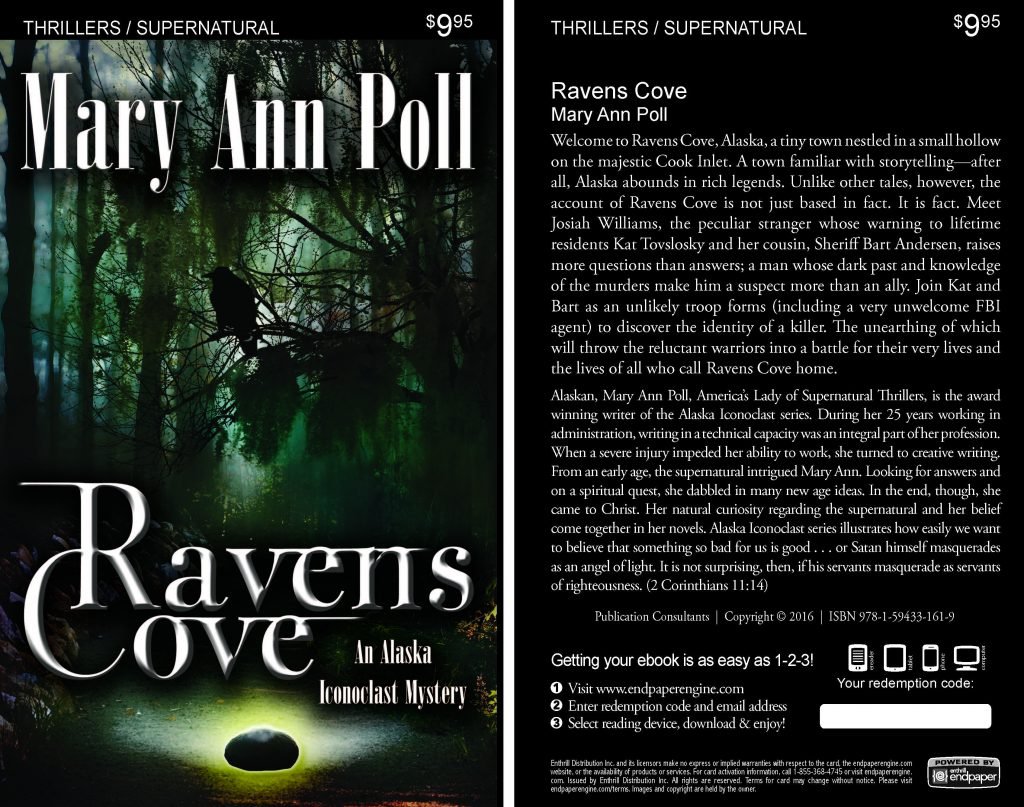

More NetGalley Mary Ann Poll

Mary Ann Poll

Bumppo

Bumppo

Computer Spell Checkers

Computer Spell Checkers Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email

Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email 2014 Spirit of Youth Awards

2014 Spirit of Youth Awards Book Signings

Book Signings

Blog Talk Radio

Blog Talk Radio Publication Consultants Blog

Publication Consultants Blog Book Signings

Book Signings

Don and Lanna Langdok

Don and Lanna Langdok Ron Walden

Ron Walden Book Signings Are Fun

Book Signings Are Fun Release Party Video

Release Party Video

Erin’s book,

Erin’s book,  Heather’s book,

Heather’s book,  New Books

New Books