I keep a saltshaker on my table, like most people. It’s ordinary, nothing special. Yet hidden in those small grains is a story every reader and writer can appreciate. Salt hasn’t only flavored food—it has flavored language itself. This is fun trivia worth sharing.

Take the word salary. It comes from the Latin salarium, which referred to payments made to Roman soldiers, sometimes with salt. From there, the word moved into the languages we read today. Every payday, whether weekly or monthly, carries a reminder of salt in the word salary. Writers use that word without a second thought, but its history tells us much about how words preserve stories.

Take the word salary. It comes from the Latin salarium, which referred to payments made to Roman soldiers, sometimes with salt. From there, the word moved into the languages we read today. Every payday, whether weekly or monthly, carries a reminder of salt in the word salary. Writers use that word without a second thought, but its history tells us much about how words preserve stories.

Expressions about salt peppers our speech. When someone is “worth their salt,” we mean they are competent and valuable. The phrase reaches back to the time when salt stood as payment. In that way, language becomes a history book. Every time we use such expressions, we read echoes of older worlds.

Even being “salty” has shifted meaning through centuries of writing. At first, it described sailors weathered by sea life, a phrase you can find in maritime journals. Later, in literature, it meant someone witty or sharp-tongued. Today, it means someone cranky or annoyed, especially in online writing. The word changed its flavor over time, and written records let us trace that journey.

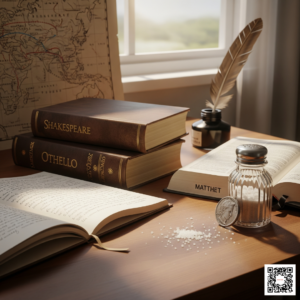

Salt found its way into books as well. Shakespeare used salt both literally and figuratively. In Othello, he spoke of “the salt of common tears.” In Measure for Measure, he wrote of “the salt of most just displeasure.” To him, salt represented deep emotion, whether sorrow or anger. Writers since have borrowed from that tradition, sprinkling salt as a metaphor whenever they needed extra bite.

Even the Bible carried salt into our reading lives. Jesus called his followers “the salt of the earth” in the Book of Matthew. The phrase now stands as one of the most widely recognized compliments in the English-speaking world. Writers, preachers, and poets have carried it forward for centuries.

Salt also helped preserve not only food but also words. In ancient times, scrolls and manuscripts traveled along the same trade routes as salt. Caravans that hauled blocks of it across deserts often carried papyrus and parchment as well. In this way, salt and words journeyed side by side, each vital to survival—one for the body, the other for the mind.

I enjoy trivia like this because it reminds me of how language works. Writers give us words, but history keeps seasoning them. What began as a soldier’s ration ends up in our novels, poems, and conversations. The next time you see the word salary in print, you’ll know you’re also seeing salt.

Fun trivia connects us with both food and language, with both taste and text. It makes the ordinary feel extraordinary. Salt no longer measures wealth, yet it still enriches our speech. When we pass the shaker at dinner, we’re also passing along centuries of human storytelling.

This is why I love sharing trivia tied to reading and writing. It gives us more than facts—it gives us perspective. Our language is a living library, where even small words like salt hide long adventures. Writers may not get paid in salt anymore, but their words remain worth every grain.

That’s the heartbeat of my new book, The Power of Authors: A Rallying Cry for Today’s Writers to Recognize Their Power, Rise to Their Calling, and Write with Moral Conviction, written with Lois Swensen and a foreword by Jane L. Evanson, PhD, Professor Emerita at Alaska Pacific University. It launches this September. You’ve been reading its heartbeat in these messages—soon you’ll be able to hold the book in your hands.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them. Release Party

Release Party Web Presence

Web Presence Book Signings

Book Signings Facebook Profile and Facebook Page

Facebook Profile and Facebook Page Active Social Media Participation

Active Social Media Participation Ebook Cards

Ebook Cards The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

Costco Book Signings

Costco Book Signings eBook Cards

eBook Cards

Benjamin Franklin Award

Benjamin Franklin Award Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex.

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex. Correction:

Correction: This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, <

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, < We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

Time and Tide

Time and Tide

ReadAlaska 2014

ReadAlaska 2014 Readerlink and Book Signings

Readerlink and Book Signings

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores.

When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores. More NetGalley

More NetGalley Mary Ann Poll

Mary Ann Poll

Bumppo

Bumppo

Computer Spell Checkers

Computer Spell Checkers Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email

Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email 2014 Spirit of Youth Awards

2014 Spirit of Youth Awards Book Signings

Book Signings

Blog Talk Radio

Blog Talk Radio Publication Consultants Blog

Publication Consultants Blog Book Signings

Book Signings

Don and Lanna Langdok

Don and Lanna Langdok Ron Walden

Ron Walden Book Signings Are Fun

Book Signings Are Fun Release Party Video

Release Party Video

Erin’s book,

Erin’s book,  Heather’s book,

Heather’s book,  New Books

New Books