Stakes are what a story’s characters risk.

Stake is different from conflict.

If someone asks if your stakes are high enough in your story, they’re asking if your characters have a lot to lose if they fail to accomplish their mission.

If the dragon will let the princess go free just by the prince asking for her, there is no conflict, and the stakes are low.

If there is a fight to the death, the stakes are high.

The prince and princess will die if the dragon wins the battle against the prince. Two lives will be lost immediately. Those are high stakes.

High stakes give meaning to your story.

It glues readers to your pages and audiences to your screenplays.

In Star Trek, The Voyage Home, the stakes are simple: If the good guys fail to restore whales to Earth’s oceans, all the world’s waters will be removed, and everything and everyone in the world will die.

The entire existence of everything doesn’t have to be what’s put on the cosmic table in a story. A riveting story can have stakes that are much smaller and more personal.

In the classic children’s book, Charlotte’s Web, the spider, Charlotte, writes praise of the pig character in her web to keep him from being turned into hams and bacon.

One pig’s life is all that’s at stake in the story. But that’s all that’s needed.

Another thing to note about stakes: almost every character, large or small, in your story should have their own.

For instance, in the autobiographical novella Douglas Avenue by the late Sarkis Atamian, the father, Mr. Stepanian, must find work despite the Depression, or his immigrant family will starve.

The stakes for his son, Garo, are to negotiate somehow an entirely new language and culture in the neighborhood and school, or he will suffer the obliteration of self-worth.

A story that satisfies your readers is one where the stakes in the story are high enough.

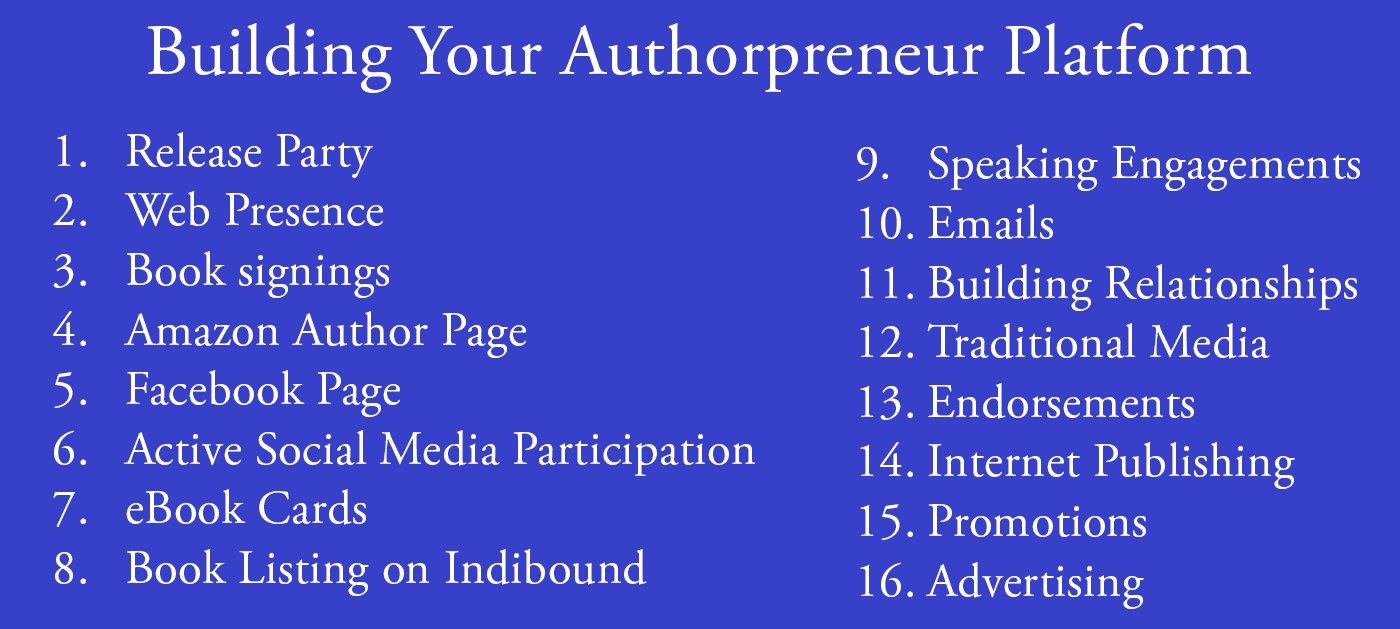

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them. Release Party

Release Party Web Presence

Web Presence Book Signings

Book Signings Facebook Profile and Facebook Page

Facebook Profile and Facebook Page Active Social Media Participation

Active Social Media Participation Ebook Cards

Ebook Cards The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

Costco Book Signings

Costco Book Signings eBook Cards

eBook Cards

Benjamin Franklin Award

Benjamin Franklin Award Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex.

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex. Correction:

Correction: This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

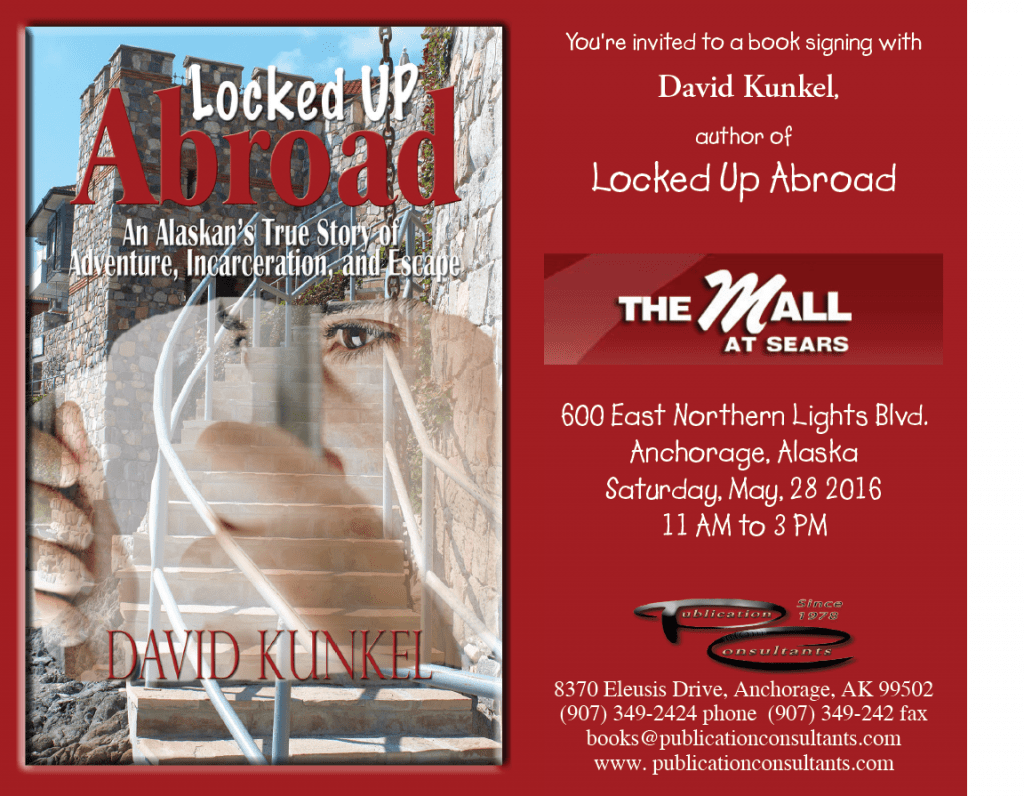

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, <

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, < We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

Time and Tide

Time and Tide

ReadAlaska 2014

ReadAlaska 2014 Readerlink and Book Signings

Readerlink and Book Signings

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores.

When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores. More NetGalley

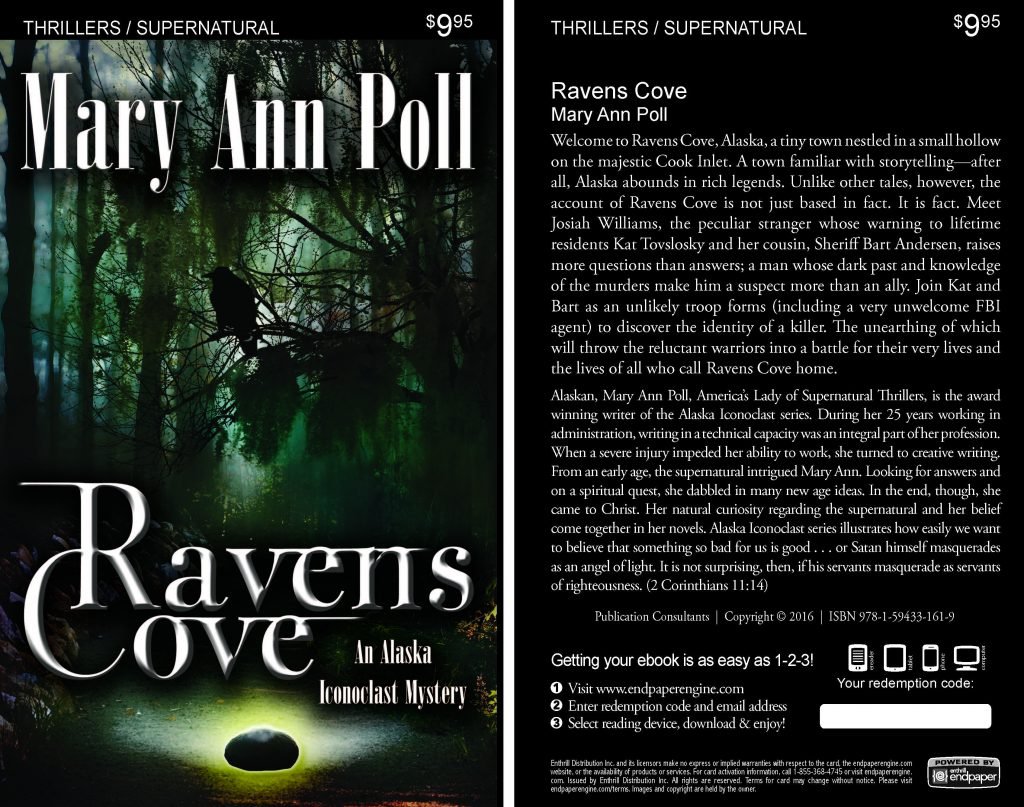

More NetGalley Mary Ann Poll

Mary Ann Poll

Bumppo

Bumppo

Computer Spell Checkers

Computer Spell Checkers Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email

Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email 2014 Spirit of Youth Awards

2014 Spirit of Youth Awards Book Signings

Book Signings

Blog Talk Radio

Blog Talk Radio Publication Consultants Blog

Publication Consultants Blog Book Signings

Book Signings

Don and Lanna Langdok

Don and Lanna Langdok Ron Walden

Ron Walden Book Signings Are Fun

Book Signings Are Fun Release Party Video

Release Party Video

Erin’s book,

Erin’s book,  Heather’s book,

Heather’s book,  New Books

New Books