Charlotte Brontë and her sisters faced a 19th-century society that often repressed women’s voices. When Jane Eyre was first published in 1847, it was under the guise of Currer Bell, an ambiguous name that provided a shield, allowing the novel to be judged free from the gender biases of the time.

Adopting a male pseudonym was common for female writers seeking to ensure their works were taken seriously. The Brontë sisters, each with their male pen name, collectively published a volume of poetry before their novels came out. The choice of the name Currer was thought to be derived from Currer Ellis and Co., a firm in the same business as their father, and Bell, perhaps an Anglicization of their mother’s maiden name, Branwell, was calculated. These names were not randomly plucked but chosen with intention and meaning, weaving a deeper story behind the novels we hold dear.

The revelation of Charlotte Brontë’s true identity brought a mixture of scandal and admiration. Imagine the 19th-century readers, their eyes widening in disbelief as the author they presumed to be a man was unveiled as a woman. This unmasking didn’t harm Brontë’s career, fortunately; instead, it amplified the power of Jane Eyre, with many readers feeling a renewed connection to the novel’s strong-willed heroine, knowing she was birthed from the mind of a woman fighting her societal constraints.

The world of pseudonyms is not just confined to women hiding their gender. There are stories of authors who adopted alter egos to write in different genres or to escape the typecasting of their previous successes. A famous example is Samuel Clemens, who sailed under the nom de plume of Mark Twain, an identity that became as legendary as the man himself. Twain, a riverboat term meaning two fathoms deep, was as much a part of Clemens’s identity as his name.

The history of literature is dotted with such cases: Lewis Carroll, known to friends and family as Charles Dodgson, who ventured down the rabbit hole of children’s literature while maintaining his academic reputation; George Eliot, the pen name of Mary Ann Evans, who wanted to ensure her works were judged by their literary merit rather than her gender; and Robert Galbraith, a contemporary mask for J.K. Rowling, when she decided to venture into the world of adult crime fiction.

What we find in these stories is not just an act of hiding but an act of liberation. Pseudonyms offered writers the freedom to explore and to be judged on the content of their prose rather than the contours of their lives. It was a dance of shadows and light, where the essence of an author could be distilled into the characters they brought to life, unhindered by the world’s judgments.

This journey through the alcoves of pseudonymity reveals a side of literature that is as human as it is fascinating. It reminds us that behind every book, there is an author, and sometimes, behind an author, there is a story just as compelling as the ones they write.

So, next time a book is picked up, it might be worth pondering the name that graces its cover. Is it a name born from necessity, from desire, or simply from the whim of its creator? The answer may add another layer to the story, making the reading adventure even more delightful.

We Don’t Want to Write the Laws; We Want to Publish the Books

We Believe in the Power of Authors Short Video: https://bit.ly/45z6mvf

Writers Reshape the World Short Video: https://bit.ly/47glKOg

Bringing Your Book to Market Booklet: https://bit.ly/2ymDVXx

Bringing Your Book to Market Short Video: https://bit.ly/3Q3g2JD

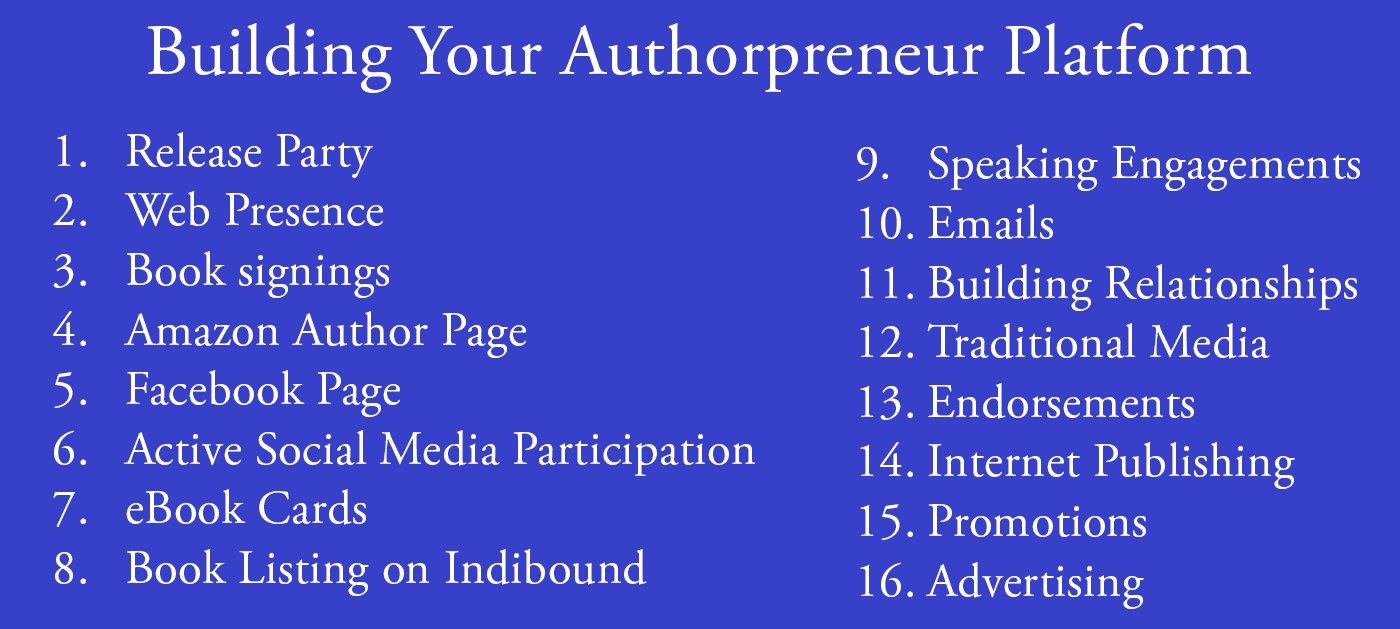

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them. Release Party

Release Party Web Presence

Web Presence Book Signings

Book Signings Facebook Profile and Facebook Page

Facebook Profile and Facebook Page Active Social Media Participation

Active Social Media Participation Ebook Cards

Ebook Cards The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

Costco Book Signings

Costco Book Signings eBook Cards

eBook Cards

Benjamin Franklin Award

Benjamin Franklin Award Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

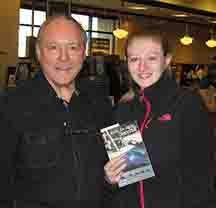

Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex.

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex. Correction:

Correction: This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

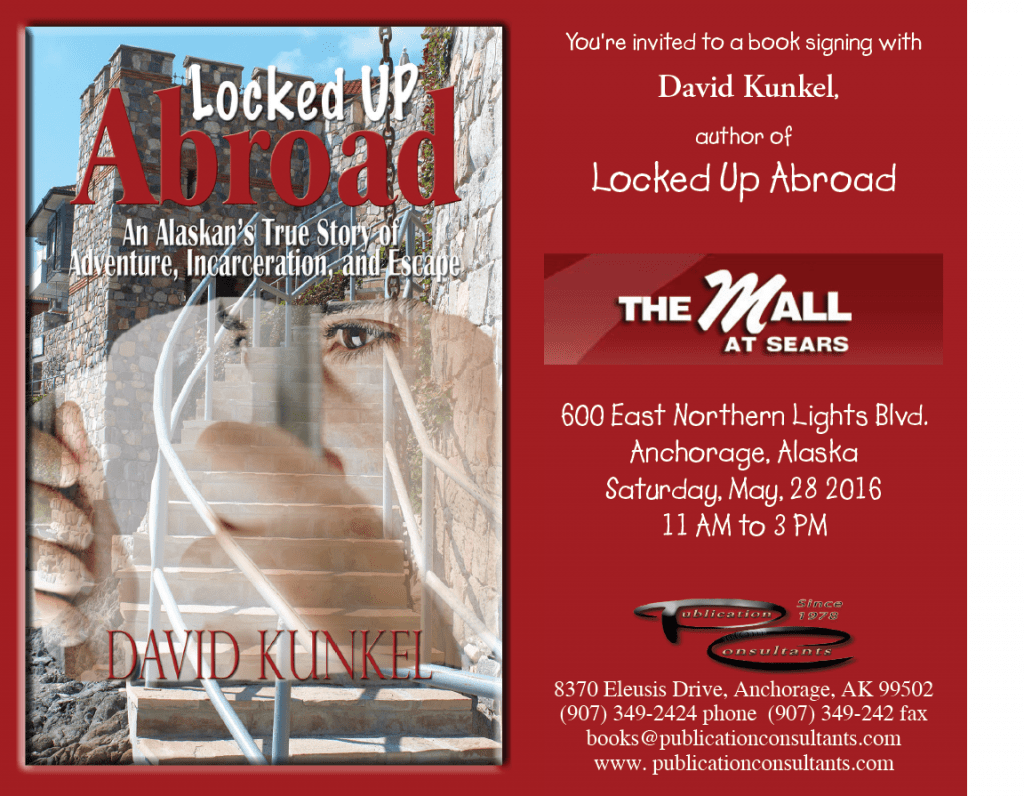

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, <

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, < We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

Time and Tide

Time and Tide

ReadAlaska 2014

ReadAlaska 2014 Readerlink and Book Signings

Readerlink and Book Signings

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores.

When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores. More NetGalley

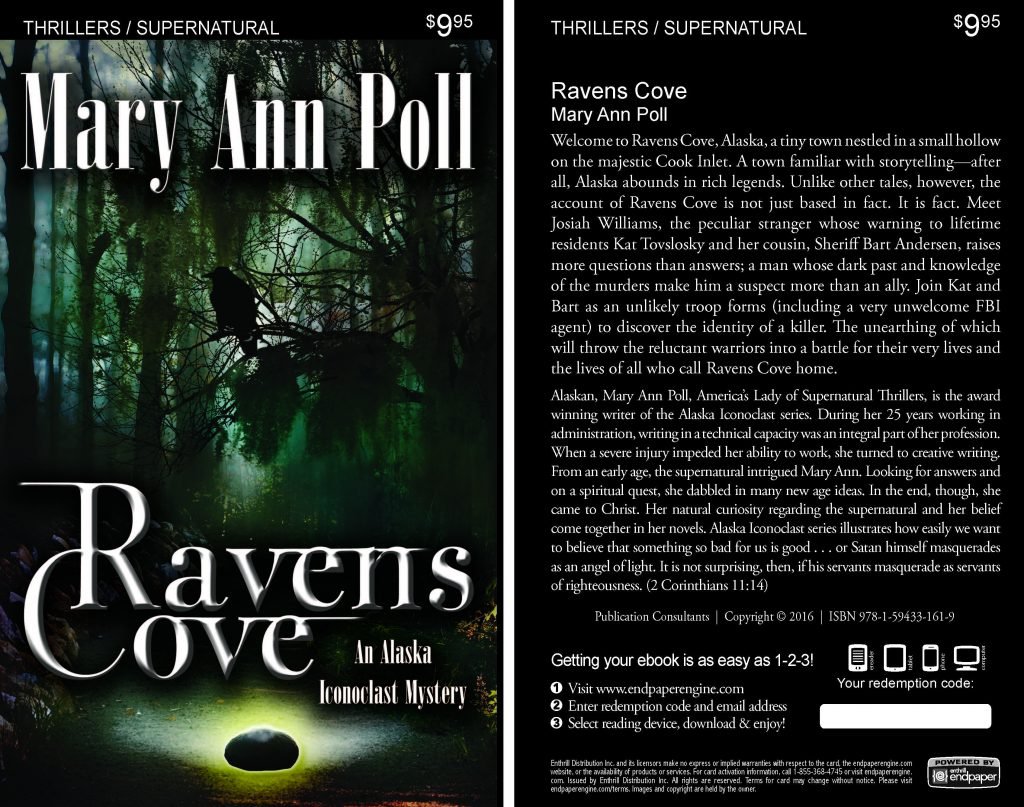

More NetGalley Mary Ann Poll

Mary Ann Poll

Bumppo

Bumppo

Computer Spell Checkers

Computer Spell Checkers Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email

Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email 2014 Spirit of Youth Awards

2014 Spirit of Youth Awards Book Signings

Book Signings

Blog Talk Radio

Blog Talk Radio Publication Consultants Blog

Publication Consultants Blog Book Signings

Book Signings

Don and Lanna Langdok

Don and Lanna Langdok Ron Walden

Ron Walden Book Signings Are Fun

Book Signings Are Fun Release Party Video

Release Party Video

Erin’s book,

Erin’s book,  Heather’s book,

Heather’s book,  New Books

New Books