Valerie Winans: Dog’s Best Friend

Author Masterminds Member

I love snow! I love the wet, the cold, the soft and fluffy, the hard and crystal like. I love snow. I like to push my face down deep into a snow bank and rub my face back and forth. The only thing better than that is to roll on my back in the snow. It’s heaven, and I was having a heavenly time in the fresh snow when I saw the snow moving near the corner of the shed. It was more like a wavy motion than just moving. It was like looking at the pavement on a hot day. I had to go check this out. I approached cautiously, but suddenly I felt suction pulling me into the waving snow. The next sensation was falling, and then suddenly I burst through the snow and stood next to a big white building that looked nothing like our shed.

There was a man in black robes calling me, but he was calling me Barry. He’s confused. My name is not Barry. He bent over, picked up some snow, made it into a ball, and threw it. Yup! I’m in. Just when I got the snowball in my mouth it disappeared of course, and I turned to see the nice man in the black robes making and throwing another one. This is a fun man. I like him even if he dresses funny and calls me Barry. I heard another black robed man call the snowball thrower Michael. After a fun time chasing snowballs, Michael took me to a place in the big white building where there were other dogs. They all seemed to know me, but could sense my reticence. Much sniffing, and even some licking, ensued. I realized these dogs were good friendly dogs, and I soon curled up with them for a nap.

Some animals, and for that matter people as well, are uniquely made for specific things. Greyhounds run well. They are built for that. Camels feel most at home in the desert where their hoofs take them easily through sand, and they are able to go for long periods without water. I am one of the original St. Bernard dogs, named for the saint by the same name, and well suited to living in the mountains, moving around in the snow, and sniffing out those in distress. We are called “bari” by travelers. It means “little bear” in German. Us Bari’s were given to the monks of the Saint Bernard pass by some wealthy noblemen in the 1700’s. The monks soon figured out what good workers we were. We could pull a sled or carry loads on our backs. I never once carried a little barrel of brandy around my neck, but I have seen pictures of St. Bernards like that. I think that the barrel thing was just for looks – not really very useful.

The monks at the monastery worked with us, and played games with us encouraging us to find things in the snow. We also walked the mountain trails with them until we knew those trails like the back of our paw. My favorite monk, Michael, would sometimes hide himself in order for us to find him. Finding him was exhilarating, and a huge reward for me. Michael would laugh and give me a good rub. He wasn’t the biggest of the monks, tall and thin, dark curly hair, and dark eyes with a sparkle in them. It wasn’t his stature that was important; it was his nature. A one word description of him would be joyful. Michael was always happy. The best thing about his frame of mind is – it was contagious. When Michael walked into a room it was immediately a better place.

Our home was very high in the mountains on a path first made by the Romans in the first century. Pilgrims used the pass to get from northern Europe to Rome, and it was, and continues to be, a perilous journey. A Roman Catholic priest, Archdeacon of Aosta, by the name of Bernard was assigned to the area including the pass. He learned of robbers who hid in the pass to rob travelers, and recruited some civilians to rout them out. He realized that the travelers had additional problems while traveling through the pass. They were caught in avalanches, storms, and wandered off of the trail into danger. He built a hospice for travelers at the top of the pass, and Augustinian monks stayed there to be close to those needing help. It was our job to help the monks with rescue of travelers. Life at the monastery was good. We had a place in the bottom level where we ate and slept, but we also were allowed to roam the rooms of the monastery as well. The monks always treated us with kindness; their care was not reserved only for travelers through the pass.

We could feel the approach of an avalanche before humans could. We knew when an avalanche had occurred from our place in the monastery, and we would go to the front door and wait for the monks to gear up and join us for rescue. I was out alone one day walking on the path south toward Italy. I sniffed the trail of some humans through the snow, and realized they had gone off of the trail. I continued on in their direction, and when I found them I tried to lead them back to the hospice. There were six of them, and I knew if they continued on the way they were going they were headed for a drop off. I barked at them and dashed back the way I had come. I kept doing that until they got the idea that I wanted them to turn around. The six men argued whether or not they should reverse their travel, but finally decided to follow me. As we plodded along back toward the hospice I sensed that there was an avalanche coming and stopped. This caused the humans to start arguing again about whether to follow me on another reversal of direction or to go on to the hospice. I whined and did everything I could to communicate that we had to go back the way we had come. Three of the humans continued toward the hospice, and the rest followed me. A short time passed before we could hear the roar of the avalanche. The men with me began to pray as we all ran back toward the avalanche because they realized their companions were undoubtedly buried in the snow and ice. I left the men at the avalanche site, returned to the hospice, and convinced the monks to follow me to the rescue of the humans.

When we got to the avalanche I put my nose to work, and very soon found the scent of a human under the snow. One of the monks poked a stick down through the snow and announced that there was someone about six feet down. The monks dug away as fast as they could, and soon came to a human, and he was alive! We found a second spot where a human was buried in snow, and we were able to pull him out alive as well. The third man was later found at the base of the avalanche. The power of the avalanche, the snow, ice, rocks, pieces of trees, and who knows what else had pummeled this poor man all the way to the bottom of the hill. My nose told me before they dug him out that he was not a breathing human, but we recovered his lifeless body, and took everyone back to the monastery for care.

I loved my life at the monastery. The companionship of other dogs was very special to me, and the monks were very good to all of us dogs. The sense of purpose was strong, and we were praised every day by the monks for our good works. As time went on memories of my home on the little lake in Michigan were distant. Michael became my favorite human, and I am pretty sure I was his favorite as well. When he saw me he would smile, come to me, rub my coat, and hug me. He knew all my best spots to scratch. He would start behind my ears, and scratch all the way down my neck to my shoulders and back. Human touch – a super sign of their love.

There came a day when my experience with human touch was not one of love. I was out on patrol by myself, and I felt an avalanche. When it stopped I ran as fast as I could toward the site. As soon as I got there I got a human scent. I located where the human was as fast as I could and started digging. When I got near the face I started licking the snow away. I kept saying to myself, “breathe human, breathe.” All of a sudden he opened his eyes and started screaming at me and flailing about. I tried to comfort him by laying down next to him to keep him warm until help could come.

All of a sudden he had a shiny metal object in his hand, and he plunged it into my side. The pain was excruciating. The poor man was out of his mind. He did not know what he was doing. I tried to give him aid again, and again I was stabbed. I was so confused. Why was this human acting this way? He stabbed me once more before the monks who had heard the avalanche arrived. I licked their hands as they lifted me to a stretcher to let them know it was okay. I was just trying to save the man. Back at the monastery, the monks cleaned and bound my wounds. They wrapped the man in warm blankets, and gave him hot tea. I later learned that he thought I was a wolf trying to kill him. No wonder he stabbed me. He was sorry for hurting me, and I was happy to have saved him.

I continued to find humans in trouble and save them. They say that I saved more than 40 people. Is that a lot? After many years on the mountain it became harder for me to keep up with the younger dogs. The monks would pat me and call me “old boy.” What’s up with that?

After sleeping in one morning, I wandered outside for a sniff, and I saw some wavy movement in the snow. Where have I seen that before? I approached and once again felt the sucking pull. I felt as if I was falling, and I burst through the snow to find myself back at my first home. There’s the shed, the house, and the lake. I ran to the lake to the end of the dock, and looking down there was my old self.

I was no longer an old “bari,” but a young beagle.

Remington Beagle was home again.

Barry St. Bernard was first published with Readers and Writers Book Club: https://readersandwritersbookclub.com.

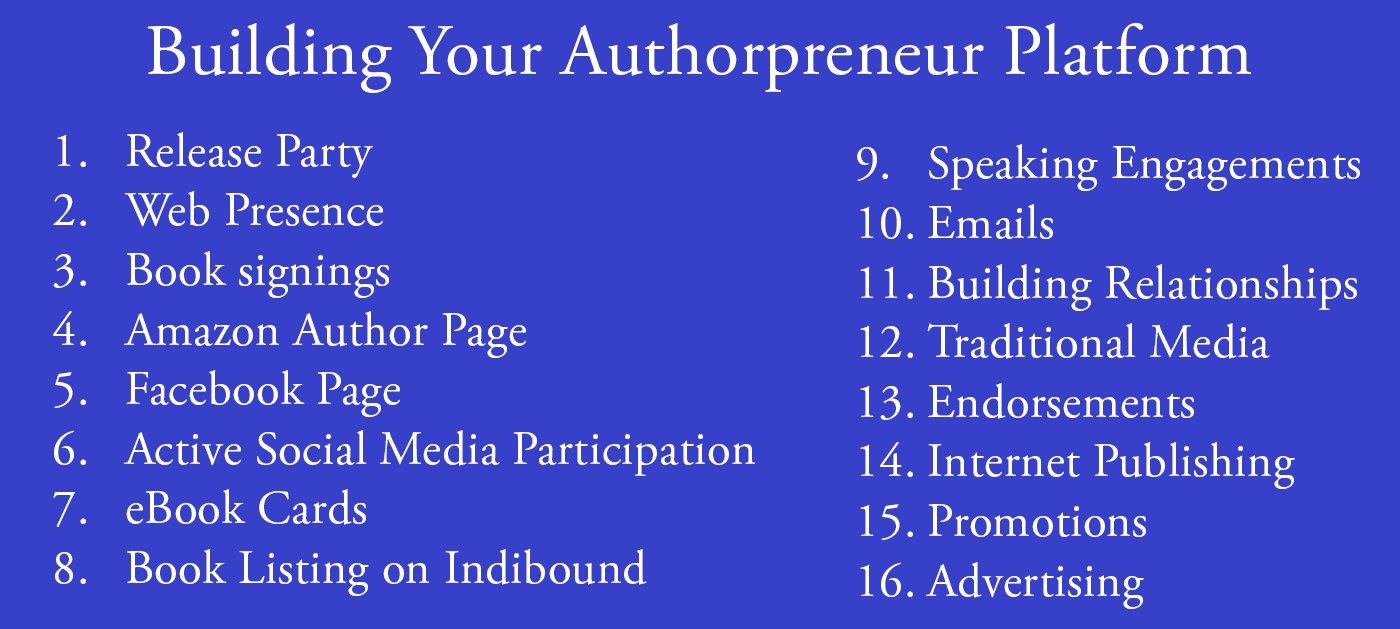

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them. Release Party

Release Party Web Presence

Web Presence Book Signings

Book Signings Facebook Profile and Facebook Page

Facebook Profile and Facebook Page Active Social Media Participation

Active Social Media Participation Ebook Cards

Ebook Cards The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

Costco Book Signings

Costco Book Signings eBook Cards

eBook Cards

Benjamin Franklin Award

Benjamin Franklin Award Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex.

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex. Correction:

Correction: This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

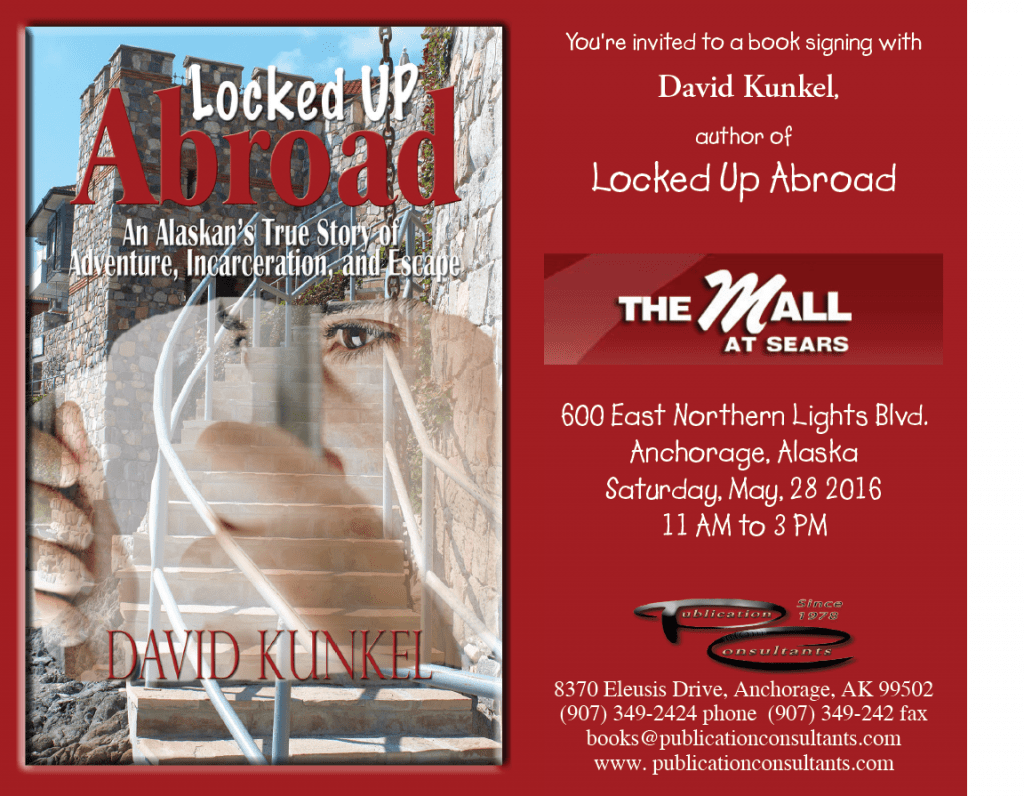

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, <

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, < We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

Time and Tide

Time and Tide

ReadAlaska 2014

ReadAlaska 2014 Readerlink and Book Signings

Readerlink and Book Signings

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores.

When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores. More NetGalley

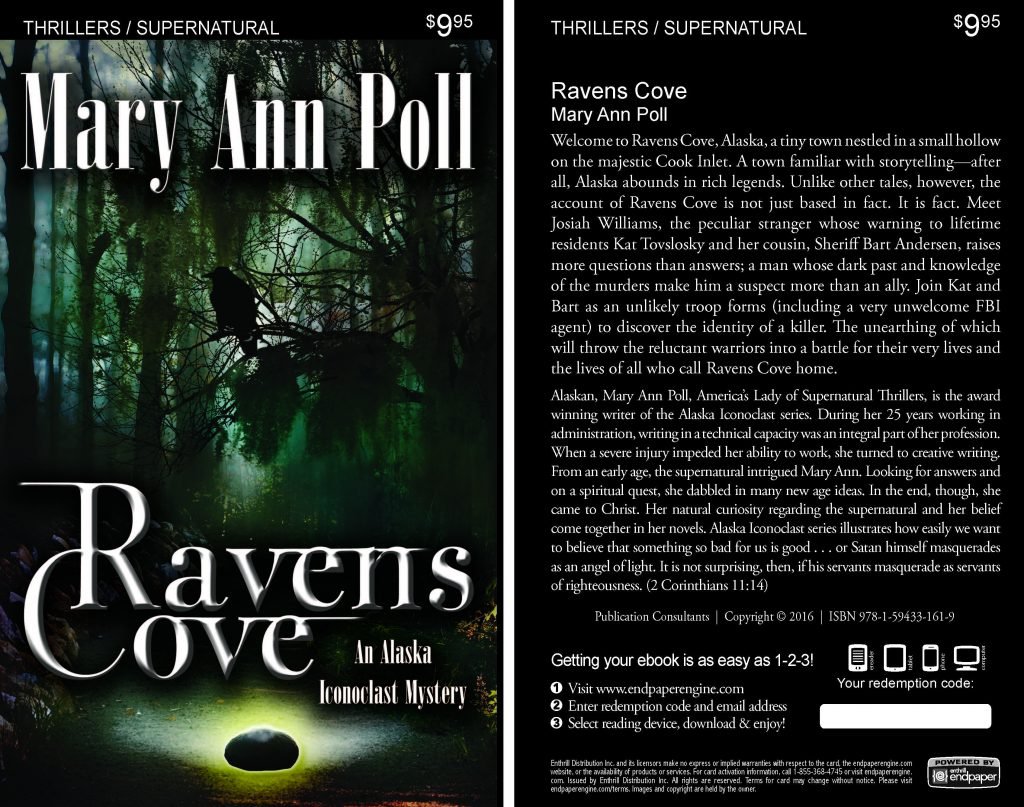

More NetGalley Mary Ann Poll

Mary Ann Poll

Bumppo

Bumppo

Computer Spell Checkers

Computer Spell Checkers Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email

Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email 2014 Spirit of Youth Awards

2014 Spirit of Youth Awards Book Signings

Book Signings

Blog Talk Radio

Blog Talk Radio Publication Consultants Blog

Publication Consultants Blog Book Signings

Book Signings

Don and Lanna Langdok

Don and Lanna Langdok Ron Walden

Ron Walden Book Signings Are Fun

Book Signings Are Fun Release Party Video

Release Party Video

Erin’s book,

Erin’s book,  Heather’s book,

Heather’s book,  New Books

New Books