“You don’t start out writing good stuff. You start out writing crap and thinking it’s good stuff, and then gradually you get better at it.”

Octavia Butler said this. She meant it. She lived it.

Writers love to quote the part about getting better. They skip over the part where you have to think your bad writing is good long enough to keep going. That’s the truth buried in her words—most people quit because they believe what they wrote isn’t worth continuing. Butler didn’t quit. She started young, failed often, doubted herself deeply, and still showed up at the page. This isn’t a story about talent. It’s a story about time, effort, and the kind of stubbornness writers need if they hope to matter.

Writers love to quote the part about getting better. They skip over the part where you have to think your bad writing is good long enough to keep going. That’s the truth buried in her words—most people quit because they believe what they wrote isn’t worth continuing. Butler didn’t quit. She started young, failed often, doubted herself deeply, and still showed up at the page. This isn’t a story about talent. It’s a story about time, effort, and the kind of stubbornness writers need if they hope to matter.

She Didn’t Grow Up Believing She’d Be Great

Octavia Estelle Butler grew up in Pasadena, raised by a single mother who worked as a maid. Her father died when she was small. Money was tight, silence common, and she was shy enough to avoid conversation. The local library gave her an escape—rows of books, stories that weren’t hers, and a corner desk where she could disappear.

She began writing science fiction tat she age of 10. By 12, she had a typewriter. Not new. Not hers. One her mother bought secondhand from a white woman she cleaned for. Butler punched out stories anyway. Spaceships, time travelers, characters who looked more like her than anything she found in the stacks.

But getting better took time. Years of rejection followed. She worked temporary jobs—telemarketing, warehouse shifts, potato chip packing—and wrote in the hours left over. Editors said her stories were too strange. Too Black. Too female. One editor told her Black women didn’t read science fiction. She kept writing.

When Kindred came out in 1979, it wasn’t because she had finally mastered the market. It was because she had stopped trying to please it.

A Wall of Words to Keep Her Going

Even after publication, doubt stayed close. Success didn’t quiet it. Instead of fighting fear, Butler surrounded herself with proof that she was still in the fight. She tacked handwritten affirmations on her walls. Some were declarations. Others were demands.

“I am a best-selling writer.”

“My books will be read by millions.”

“This is my life. I write.”

She read those lines daily. Not because she believed them. Because she needed to. Those notes weren’t motivational fluff. They were survival tactics. Tools she used to outlast doubt.

She had help along the way. Harlan Ellison, who never minced words, told her to apply to the Clarion Writers Workshop. She got in. Clarion changed everything. She met people who saw her writing not as a novelty—but as serious work. That recognition gave her footing. From there, she climbed.

Her Work Didn’t Just Entertain—It Interrogated

Butler’s writing didn’t follow trends. It warned. It tested. It told truths readers weren’t always ready for. Kindred pulled a modern Black woman into slavery, not to imagine a past, but to make it impossible to ignore. Parable of the Sower, written in the 1990s, read like prophecy. A broken America. Ecological collapse. A charismatic demagogue rising to power with a slogan eerily close to one heard on stages years later.

Butler didn’t claim she could predict the future. She just paid attention. Her characters weren’t superheroes. They were vulnerable. Sometimes broken. Often forced to survive by changing when no one else would. She showed how adaptation is power. How empathy is strategy. How fiction, when done right, can hold up a mirror sharper than nonfiction ever could.

She Didn’t Write to Be Celebrated. She Wrote to Be Heard.

In 1995, Butler became the first science fiction author to win a MacArthur “Genius Grant.” By then, her shelves held awards. Hugo. Nebula. Locus. But those honors never mattered more than the next page. She stayed humble. Private. She kept writing.

Her legacy rests not in how many copies she sold, but in how many writers she gave permission to begin—without polish, without praise, without certainty.

Writers Like Her Leave More Than Books

Butler showed that writing doesn’t begin with skill. It begins with the willingness to keep going. Anyone can start. Not everyone does. Fewer still keep going when it feels like no one’s listening.

She kept going. Through rejection. Through self-doubt. Through loneliness. And what came of it were stories that rewired readers, redefined genres, and offered truth in places no one thought to look.

Read Octavia Butler

Start with Kindred. Then try Parable of the Sower. Read her stories. Read her notes to herself. Let them remind you that bad writing is how good writing starts.

Then write. Don’t wait for genius. Don’t chase perfect. Sit down, press the keys, and give yourself permission to write something ugly. Something true.

Someone will thank you for it one day. Maybe even you.

Help Us Spread the Word

If this message inspired, informed, or gave something worth thinking about, please consider sharing it. Every share helps grow a community of readers and writers who believe in the power of stories to make a difference.

Please invite others to join us by using this link: www.publicationconsultants.com/newsletter/

Thank you. We’re always glad to have one more voice in the conversation.

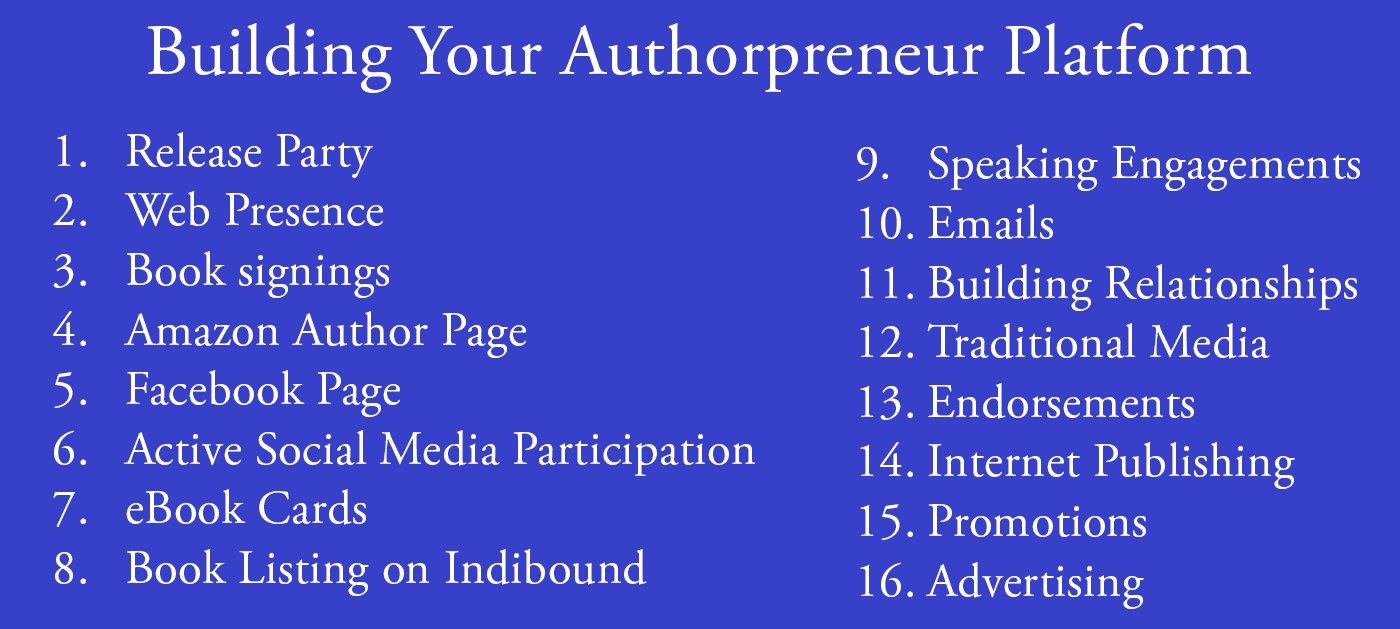

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. Author Campaign Method (ACM) of sales and marketing is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authorpreneurs who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for them. Release Party

Release Party Web Presence

Web Presence Book Signings

Book Signings Facebook Profile and Facebook Page

Facebook Profile and Facebook Page Active Social Media Participation

Active Social Media Participation Ebook Cards

Ebook Cards The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

The Great Alaska Book Fair: October 8, 2016

Costco Book Signings

Costco Book Signings eBook Cards

eBook Cards

Benjamin Franklin Award

Benjamin Franklin Award Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Jim Misko Book Signing at Barnes and Noble

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex.

Cortex is for serious authors and will probably not be of interest to hobbyists. We recorded our Cortex training and information meeting. If you’re a serious author, and did not attend the meeting, and would like to review the training information, kindly let us know. Authors are required to have a Facebook author page to use Cortex. Correction:

Correction: This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

This is Publication Consultants’ motivation for constantly striving to assist authors sell and market their books. ACM is Publication Consultants’ plan to accomplish this so that our authors’ books have a reasonable opportunity for success. We know the difference between motion and direction. ACM is direction! ACM is the process for authors who are serious about bringing their books to market. ACM is a boon for serious authors, but a burden for hobbyist. We don’t recommend ACM for hobbyists.

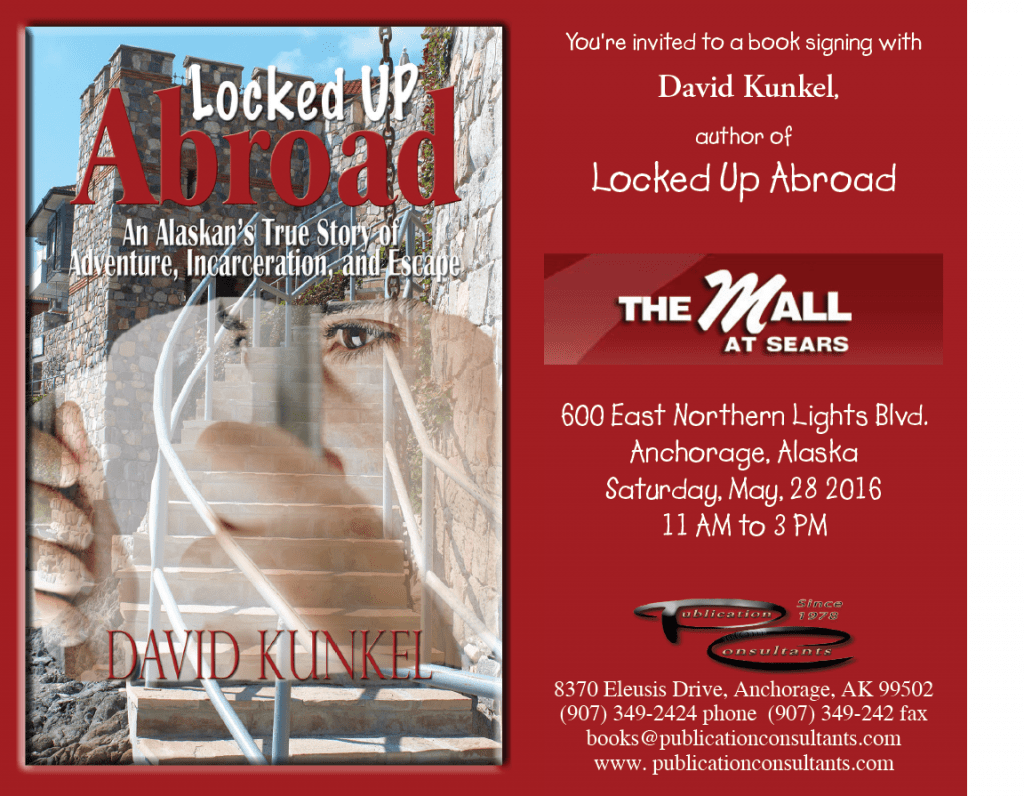

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, <

We’re the only publisher we know of that provides authors with book signing opportunities. Book signing are appropriate for hobbyist and essential for serious authors. To schedule a book signing kindly go to our website, < We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

We hear authors complain about all the personal stuff on Facebook. Most of these complaints are because the author doesn’t understand the difference difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. Simply put, a profile is for personal things for friends and family; a page is for business. If your book is just a hobby, then it’s fine to have only a Facebook profile and make your posts for friends and family; however, if you’re serious about your writing, and it’s a business with you, or you want it to be business, then you need a Facebook page as an author. It’s simple to tell if it’s a page or a profile. A profile shows how many friends and a page shows how many likes. Here’s a link <> to a straight forward description on how to set up your author Facebook page.

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

Mosquito Books has a new location in the Anchorage international airport and is available for signings with 21 days notice. Jim Misko had a signing there yesterday. His signing report included these words, “Had the best day ever at the airport . . ..”

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

The Lyin Kings: The Wannabe World Leaders

Time and Tide

Time and Tide

ReadAlaska 2014

ReadAlaska 2014 Readerlink and Book Signings

Readerlink and Book Signings

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Bonnye Matthews Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview

Rick Mystrom Radio Interview When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores.

When he published those overseas blogs as the book The Innocents Abroad, it would become a hit. But you couldn’t find it in bookstores. More NetGalley

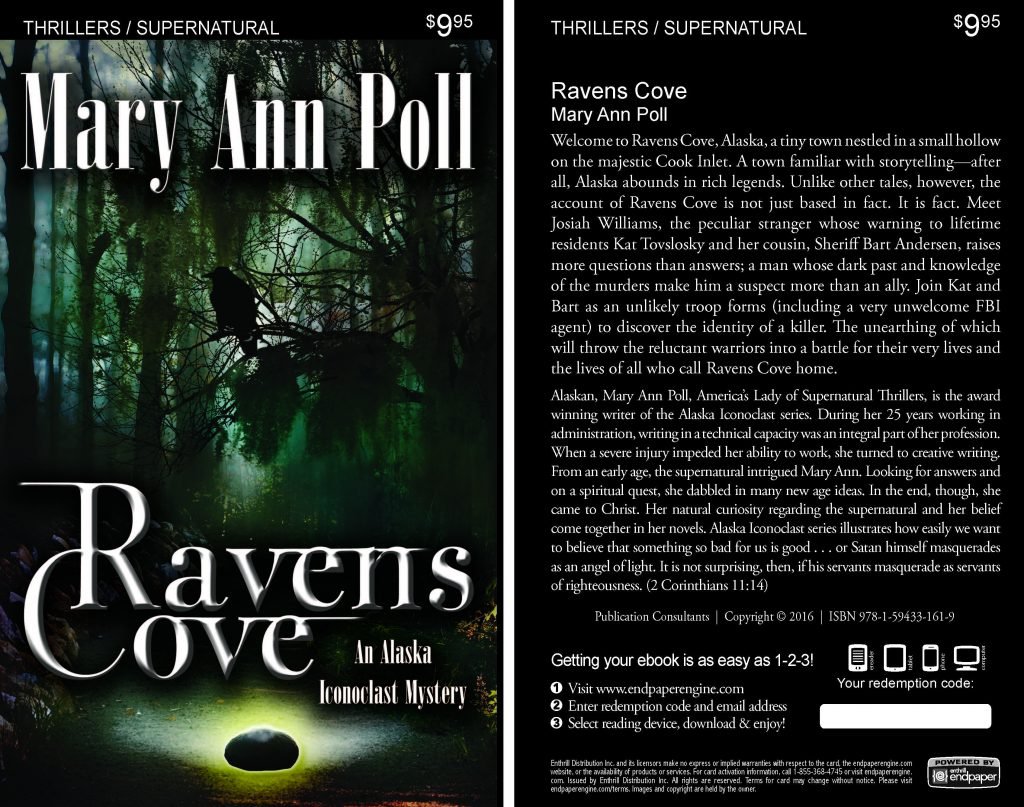

More NetGalley Mary Ann Poll

Mary Ann Poll

Bumppo

Bumppo

Computer Spell Checkers

Computer Spell Checkers Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email

Seven Things I Learned From a Foreign Email 2014 Spirit of Youth Awards

2014 Spirit of Youth Awards Book Signings

Book Signings

Blog Talk Radio

Blog Talk Radio Publication Consultants Blog

Publication Consultants Blog Book Signings

Book Signings

Don and Lanna Langdok

Don and Lanna Langdok Ron Walden

Ron Walden Book Signings Are Fun

Book Signings Are Fun Release Party Video

Release Party Video

Erin’s book,

Erin’s book,  Heather’s book,

Heather’s book,  New Books

New Books